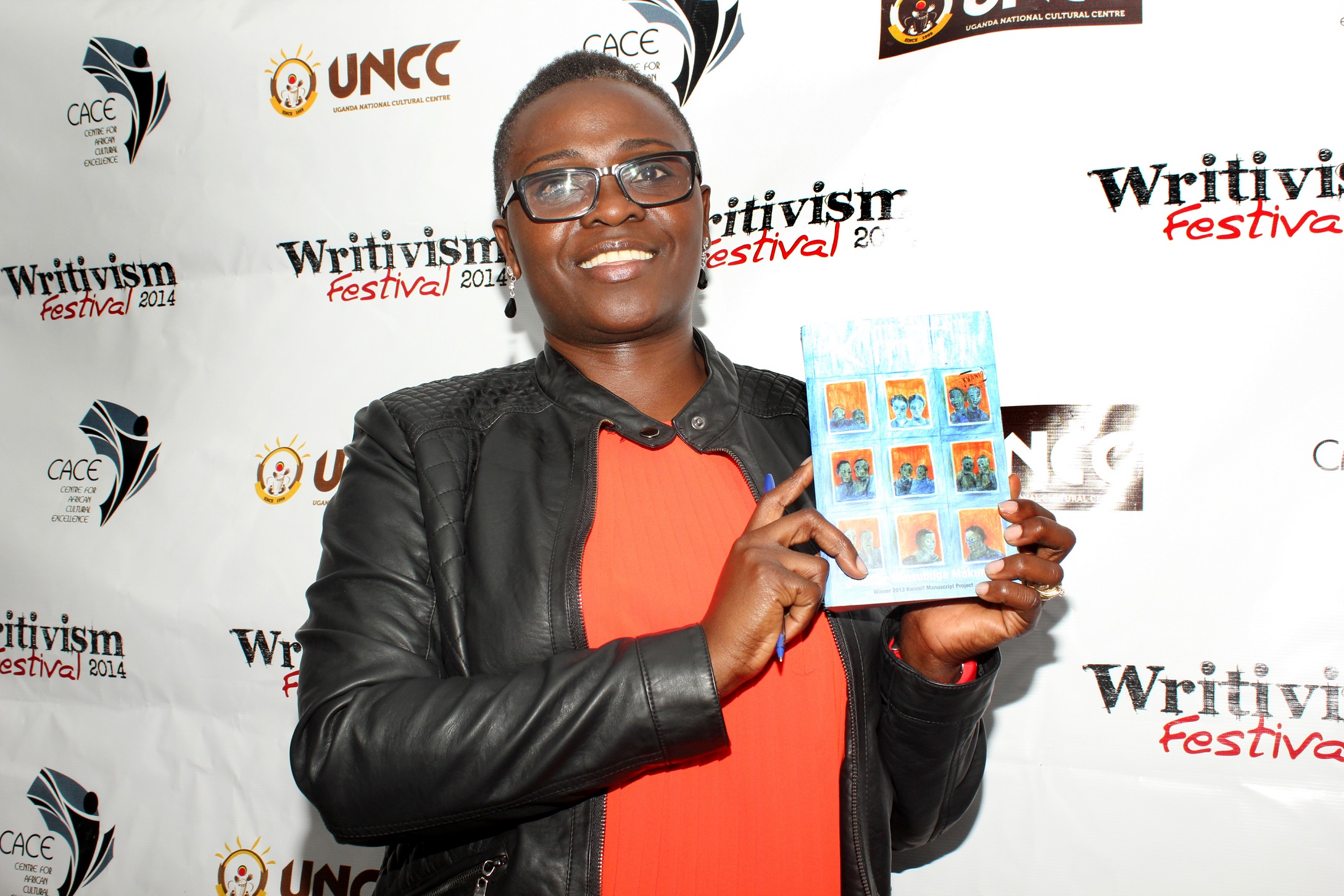

Uganda is not short on writers wielding skillful pens Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi The 2014 Commonwealth short story prize winner is in that Pick of the top BunchRead on below her story

By Richard Wetaya

If my mind serves me

right, it was Sunday, June the 22nd.

I was on my return journey to Kampala from Mbale.

Even with the rough and tumble of the road humps, I was caught up, attentive as I listened in to the Arts hour show on the BBC with Nikki Bedi.

Just when I was thinking of giving my ears a rest, Bedi announced that she would be hosting an award winning Ugandan novelist and short story writer in her show’s next half hour. At length, Bedi introduced her quest, a lady by the name of Jennifer Makumbi, born and bred in Uganda but now living and working in England.

Makumbi, an associate creative writing lecturer at Lancaster University was just fresh off her triumph in the 2014 Commonwealth short story competition.

Makumbi won the contest on strength of her short narrative entitled “Let's Tell This Story Properly”.

The judges praised Makumbi for her narrative and dramatic story telling style.

Makumbi was pitted against over 4,000 other authors with unpublished stories from the five commonwealth regions. When the scales were tipped, Makumbi walked away with the top prize of £5,000.

“Let's Tell This Story Properly” narrative is about a mourning widow who arrives at Entebbe Airport from Manchester with her husband’s casket. Unfortunately, events take an unfavourable turn and the widow is compelled to relinquish her widowhood and fight.

Makumbi has an admirable gift of gab when she speaks. Her facility in speech kept me glued throughout the interview. Her assertion that Uganda’s literary landscape is changing is true in many respects, evidenced by the literary works of talented writers such as Doreen Baingana, Beatrice Lamwaka, Jackee Batanda, Moses Isegawa and now Makumbi, who by all accounts is no novice, even if the mention seems to suggest otherwise.

It goes without saying that the above authors wield skillful pens. With Makumbi’s triumph, you can not bet against the fact that Ugandan writing will indeed be given more global showcases.

ON MAKUMBI’S WRITING JOURNEY

Makumbi started writing in earnest at age 15 in her secondary school days, first at Trinity College Nabingo, where she wrote, directed and produced a play that came third in an inter house writing competition and later at Kings college Budo.

“I first wrote when I was pretty young but I did not start to write consistently until 2001. My grandfather, Elieza Makumbi, taught me how to tell stories orally. I have so far written three plays, one novel and published three short stories. Iam about to publish a fourth short story,” Makumbi reveals.

ON INSPIRATION TO WRITE

Telling entertaining stories that rely heavily on Kiganda oral traditions and legends is Makumbi’s stock in trade.

“I love telling stories but I also have strong views about life and I have no other platform to share them. Story telling is where people like me attempt to entertain people but sneak ideas, questions, suggestions and views into the tale without seeking to preach. Part of my motivation is the desire to tell the stories from Uganda and from my immigration experience the way I know them. Oral traditions are the history and reference for my literary creativity,” Makumbi explains.

MAKING CHARACTERS COME ALIVE IN A STORY IS WHAT EVERY WRITER STRIVES FOR AND FOR MAKUMBI ITS CLOSE AS INTIMACY.

“I try to know my characters intimately. I try to spend time with them to such an extent that sometimes I even see them beyond the novel. For example, in my mind Kusi (Miisi’s daughter) in Kintu gets pregnant a year or two later after the story has ended for that is what her father once wished for. While writing I try to see, feel, smell, touch and taste the aspects of the story, as if I am right there in the story, as if Iam the character.” Makumbi says.

ON THE POOR READING CULTURE IN UGANDA.

Makumbi takes exception to the idea that Ugandans have a poor reading culture.

“I think this is a misconception. Ugandans read but not necessarily Ugandan fiction.

The consumption of newspapers and nonfiction is very high. In my view, the question is, how do we get these same readers to read and enjoy Ugandan fiction and how do we sustain their interest in local writing,” Makumbi says.

COUNSEL TO WRITERS AND THE PROSPECT OF BECOMING A HOUSEHOLD NAME.

“My advice to Ugandan writers is firstly to enjoy the writing process of their stories. Chances are that the readers will enjoy them too. Write about things that are relevant to Ugandans. Be bold, say things that people only say in their houses or in their hearts. Say these things interestingly. Do not preach: Ugandans get a lot of preaching in churches. They come to the novel to seeking suggestions. Share your drafts with other writers. Listen when they say something is not working.

For me things like becoming a household name are for musicians and film stars. There are a few author celebrities like Chimamanda Adichie and Ben Okri but that does not come to all authors,” Makumbi points out.

MAKUMBI’S ADDITIONAL WRITING LAURELS ASIDE OF THE COMMONWEALTH PRIZE

Her short story ‘The Accidental Sea’ man published in Moss side Storiesreceived commendation from the Caine Prize (2013).

The same year her manuscript, The Kintu Saga won the Kwani? Manuscript Project, a new literary project for unpublished fiction by African writers.

She has also written what she describes as a tongue in cheek short fiction, ‘Move against Kenco Foiled’ published in Renegade: the Alternative Travel Magazine.

Her short story, Malik’s Door will be published in Closure Magazine by peepal Tree Publishers. Makumbi is part of the African Reading Group ARG in Manchester.

RESPONSE TO BAD REVIEWS

Inevitably, with the attention of the media, Makumbi has not escaped the scrutiny of critics and cynics.

“I have only had a few reviews of my novel, Kintu. Thankfully so far, most of them have been positive. One review by Tom Odhiambo of Kenya’s Daily Nationwas largely positive but what he highlighted as the weaknesses of the novel, namely the presentation of masculinities, took me by surprise and I thought, ‘hm I could not have seen that coming!’All along, I had expected feminists to pick on the presentation of women, after all the most evil character Kulata is a woman. I did not expect a man to complain about the presentation of men in a novel where the point of view is majorly from a male perspective and there was no attempt to shake the status quo of the patriarchy. However, I walked away with respect for his way of reading the novel: I had learnt something about the way people read. There was however a peculiar article by New Vision’s Kalungi Kabuye. He seemed pretty angry at what he saw as me coming from Britain and proclaiming myself the literary messiah. It was a very distressing experience. To his credit, Kabuye did not pretend to review the novel. He confessed that he had neither read it, nor met me. Nonetheless, the experience taught me something about the media,” Makumbi notes.

CHALLENGES

Though Makumbi’s writing star has been rising to the ascendant, she reveals she has struggled to fight off an inconvenient disorder.

“I have mild amnesia. It is part of a larger problem but it is the amnesia that is most irritating because I forget names, faces, I forget what Iam about to do, I forget promises, and sometimes it is so bad that I forget what Iam about to say and hesitate or take long time to answer questions. Sometimes I walk past people I have met and they think I am being haughty. It is terrible when I forget what I promised to do or what I said because I just come across as a liar. Normally, I ask people I have made promises to, to remind me in an email. The worst is when I stop mid sentence as I am teaching because I have forgotten the next word. This leads to apologising that the word I was about to say has gone which is terrible for oral interviews. Normally students, because I warn them in the first class, are verysympathetic,” Makumbi reveals.

Makumbi’s calling card through her battles with Amnesia however has been her confidence.

“In many circumstances, Iam quite confident. And by this I mean that I am confident enough to confess that Iam ignorant when I am, I will take back my words if they are indefensible, I will confess that I am a bag of contradictions when I contradict myself; I will say this today because that is what I think now but tomorrow I say the other because that what I think then, I also will confess that I am insecure when my insecurities strike as they sometimes do,” Makumbi adds.

For Makumbi, it has also been hard to dispense of one sad memory about her late Dad.

“The first challenge was to come to terms with the fact that my father had lost his mind. I lost him at a point in my childhood when I still thought he was superdad. It is hard at that age to change the mindset. Mostly as a teenager you start to see weaknesses in your parents and you accept and love them as flawed beings. I never had that chance. It took me a long time to accept that, that handsome, clever, kindest, basically perfect person was gone. As a teenager I did not want friends to know about him. So I never mentioned him even though I still loved him deeply,” Makumbi says.

Makumbi’s father, a banker then, was arrested, mauled and ill-treated during Idi Amin’s barbaric regime. Though he survived, the torment gravely affected him, the upshot being him losing his mind, his job and his family.

WHO IS JENNIFER MAKUMBI?

Makumbi was born to the late Anthony Kizito Makumbi and Evelyn Nakalembe. Her parents separated when she was only 2 years old. For two years Makumbi stayed with her grandfather, the late Elieza Makumbi.

“My father, the few years I spent with him, made me read abridged forms of the English canon. He believed in western literature. He used to tell me that I was smart that if I put my mind to it, I could do anything. He would show my reports to his friends which made me work harder so that I did not embarrass him. Even when his mind was gone, he would ask whether I was doing literature at university, whether I had mastered Shakespeare’s sonnets, tragedies, comedies and tragicomedies. He was instrumental in nurturing me as a writer and Iam so lucky to have known him,” Makumbi states.

EDUCATION

Makumbi joined the Islamic University in Uganda after Budo. She qualified with a Bachelors of Arts degree, majoring in teaching English and Literature. In 2001, she joined Manchester Metropolitan University for a Masters in creative writing. In 2012 she completed her PhD in creative writing from Lancaster University. At present, she lectures in the Department of English and creative writing at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom.

LIFE AS A BALANCING ACT.

Makumbi lives in Manchester with her Husband, Damian Morris, a British Man of Jamaican extract and her son, Jordon Kiggundu Bamundaga.

On how she balances her roles as a mother and lecturer, Makumbi says her roles just merge and overlap as the day goes on

“I don’t look at myself as performing all those roles. I doubt that anyone does, really. I guessthose roles merge into each other or overlap as the day goes on. I have a diary. I write down what needs to be done for the day but it is not compartmentalized that this is what I’ll do today as wife, as mother, as this or as that. I just go. I am just me,” Makumbi says.

IN DAILY LIFE, MAKUMBI SAYS SHE DOES NOT HAVE A TYPICAL DAY.

“I don’t have a typical day really. Sometimes I get up in the morning,sit on the computer and then look up later and ask where the day has gone. Sometimes I wake up and go straight to the pool and do things according to plan. Sometimes I don’t get to do much, just dawdling about. I then apologise to my son and to my partner when they come home becauseI have been in the house all dayyetI have done nothing. A good day is when I keep to the plan in the diary or do much more than I had anticipated,” Makumbi says.

WHAT MAKUMBI IS MOST PROUD OF

“I am proud of my culture despite all its imperfections. I am proud of the food and how we prepare it traditionally, the music and dance, the traditional architecture though the old age Amasiro are not with us anymore, our dress and ofcourse our oral traditions. Perhaps this has something to do with being away from my home country; you start to appreciate and long for things you once took for granted,” Makumbi says.

LIFE WHEN MAKUMBI IS NOT WORKING.

“I love eating out. We go out to restaurants a lot with my family. I love Chinese food. Damian and I love going to the movies. I watch most of the movies that come out when I have the time because there is a sense of story in a film. I spend a lot of time swimming because I cannot do any other forms of exercise. I also spend time in the sauna, Jacuzzi and steam rooms. These are my ‘me time’ and they help me de-stress and are helpful with my health issues especially in winter. Sometimes my husband takes me to big shows and to the theatre,” Makumbi says.

Read More

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to http://masaabachronicle.com/

Comments